Joshua Sbicca’s latest book A Recipe for Gentrification: Food, Power, and Resistance in the City was released by NYU Press in July 2020. Along with Alison Hope Alkon (University of the Pacific) and Yuki Kato (Georgetown University), Dr. Sbicca co-edited contributions about gentrification’s effects on food landscapes in cities and towns across the United States and ensuing resistance efforts. Please see the below article for more details.

Dr. Sbicca recently did a radio interview for Top of Mind with Julie Rose about his food and gentrification research. The half-hour broadcast “Restaurants Setting the Table for Gentrification” aired on BYU Radio November 11, 2020.

Also in November, The Social Breakdown interviewed Dr. Sbicca and co-editor Dr. Alkon to record “SOC408 – Gentrification Through Food (Guest Edition)” as a podcast that will be used as a teaching resource/introductory resource to complex sociological topics.

Dr. Sbicca was featured in Eater’s September article “How to Track a Neighborhood’s Gentrification Through Restaurant Openings.” He was interviewed at length about looking at gentrification through both cultural and economic lenses and how issues around food intersect.

In July, The Conversation published “In changing urban neighborhoods, new food offerings can set the table for gentrification” by Drs. Sbicca, Alkon and Kato. In the article, they note that “food businesses are among the first to change in historically disinvested low-income communities and communities of color.”

Food’s contributions to gentrification are focus of new book co-edited by CSU prof

Article by Jeff Dodge. Originally published on SOURCE

The first essay in a new collection about the role that food plays in gentrification by a Colorado State University faculty member and his co-editors tells the tale of ink! Coffee in north Denver.

In fall 2017, the coffee shop set up a sign that read “ink! Coffee. Happily gentrifying the neighborhood since 2014” on one side. The other side read, “Nothing says gentrification like being able to order a cortado.”

The sign caused a controversy in the historically Black community formerly known as Five Points but now referred to as the “River North Arts District,” or RiNo, as new developments have given it a hipster vibe. Someone spray-painted the words “white coffee” on the outside of the shop in reaction to the sign.

It is one of many examples that Joshua Sbicca, an associate professor in CSU’s Department of Sociology, and his colleagues have included in A Recipe for Gentrification: Food, Power, and Resistance in the City, published July 14 by New York University Press.

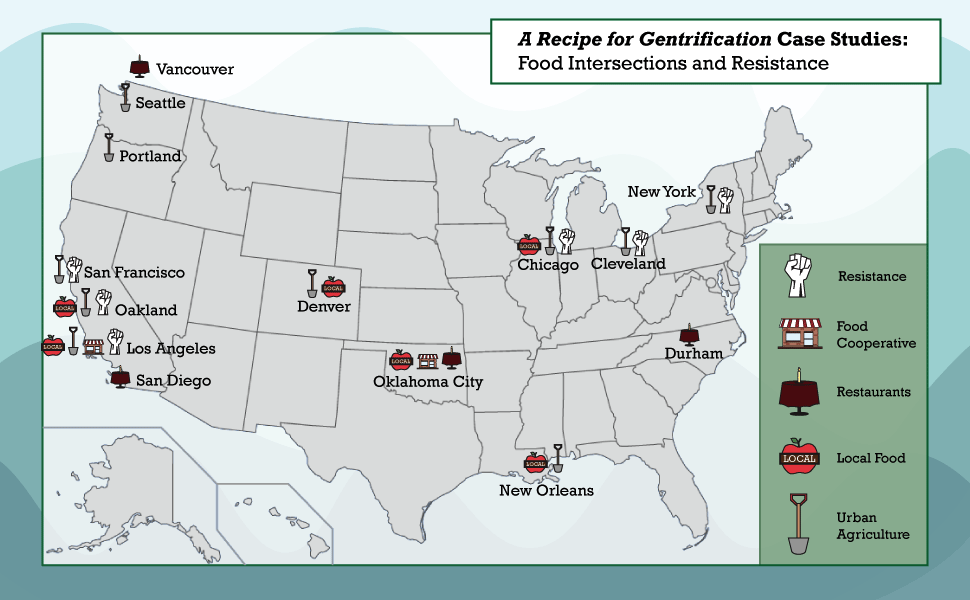

The book, which Sbicca co-edited with Alison Hope Alkon of the University of the Pacific and Yuki Kato of Georgetown University, features essays exploring the role of food in gentrification around the country, from Los Angeles to New York City, Seattle to New Orleans.

Who owns kale?

Some of the examples involve newcomers co-opting a traditional cultural dish as their own, like the San Diego restaurant that began serving gourmet “Tijuana-style” hot dogs at a counter built from a low-rider Chevy. Or the 2014 “kalegate” controversy set off when actress Tara Elders was quoted in the New York Times as saying, “New Orleans is not cosmopolitan. There’s no kale here.”

“Kale is a symbol of changing tastes, hipster tastes,” Sbicca explained. “But in New Orleans, they’ve been eating kale a long time. The question became, ‘Who owns kale?’ Food can be a flashpoint for residents when they see something that’s been a longtime staple in their diets ‘discovered’ by others.”

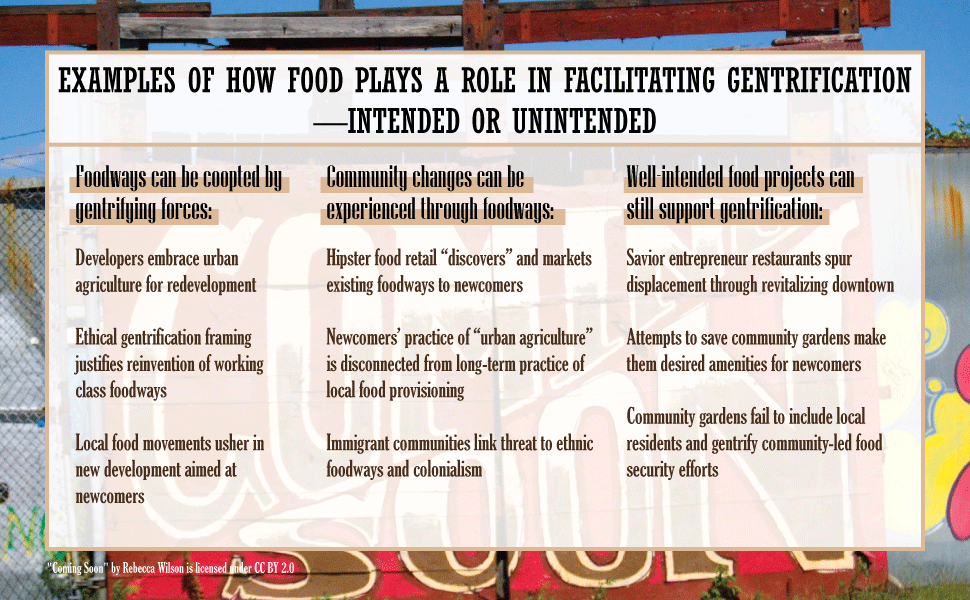

In other examples, the issue is urban agriculture, or community gardens, which can be used by developers to lure affluent buyers to an area and do not always benefit existing longtime residents.

“Often, it’s a question of ownership,” Sbicca said. “Who owns the land? If you build a capital-intensive hydroponic farm, that’s an amenity that makes it cool to live there. But unless longtime residents actually own places to grow food, or food businesses, it’s hard to resist these gentrification pressures.”

The arrival of hip new coffee shops and restaurants can lead to an influx of wealthier residents as well as higher dining costs and property values. And that can force longtime lower-income residents out, because they can no longer afford the housing — or the food.

“I would never make the case that people shouldn’t have nice restaurants or urban farms,” Sbicca said. “The complicating piece is, who controls that process? It tends to be dominated by white, upper-class people with a lot of cultural capital. There needs to be greater sharing of the wealth and power in these food spaces.”

Development and displacement

In his own essay included in the book, Sbicca writes about “The Urban Agriculture Fix: Navigating Development and Displacement in Denver.” He discusses the 10-year evolution of a former public housing site in the historically Black neighborhood known as Curtis Park, a place that was transformed into a land banking project called “Sustainability Park” and then into a condo/townhome development that includes a hydroponic farm above a high-end Japanese restaurant. The demographics of the area have flipped from majority working class people of color to majority professional class white residents.

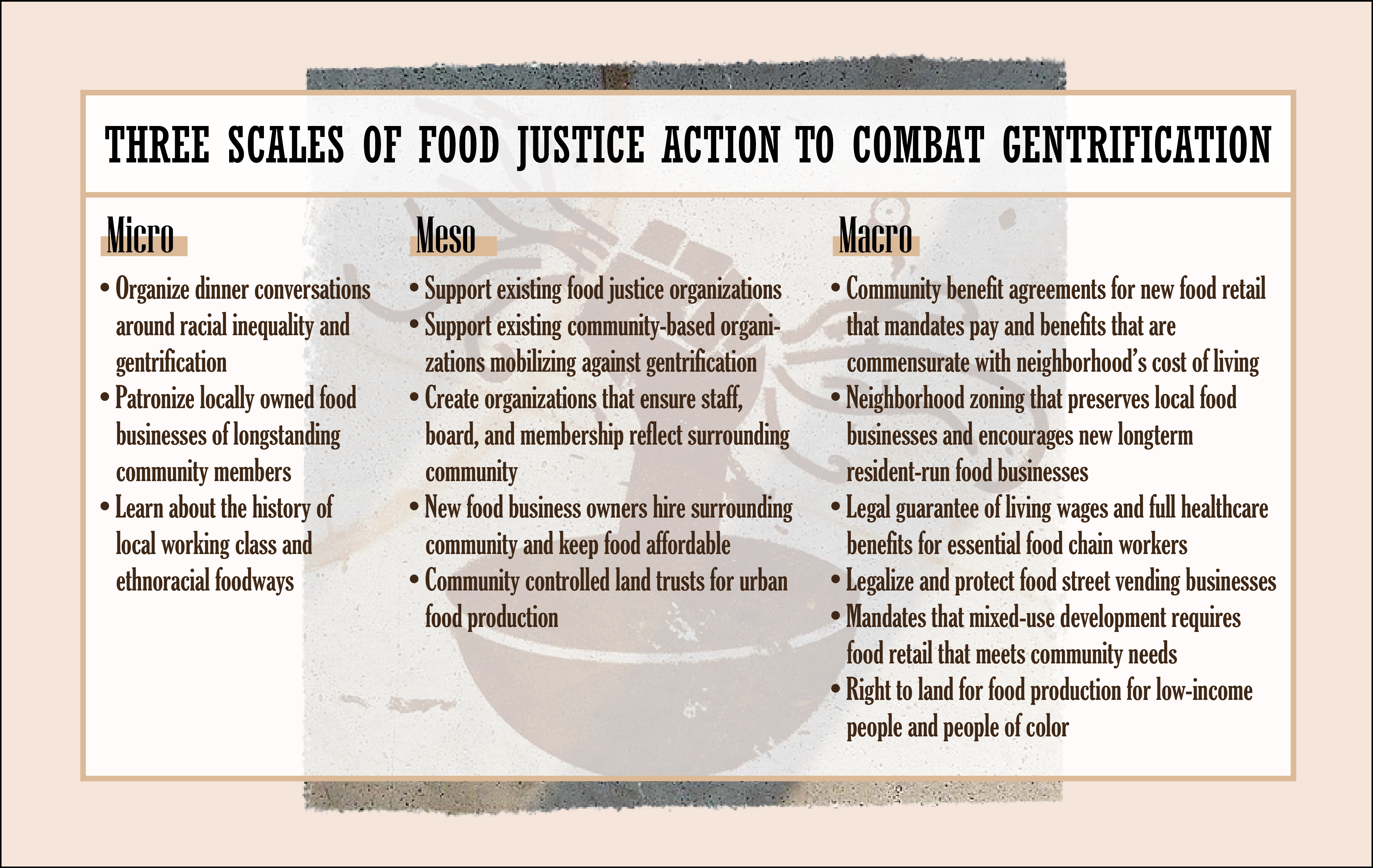

Sbicca explained that there are ways to avoid having food contribute to gentrification, such as requiring developers and new business owners to hire local workers, keep food affordable, guarantee a living wage/health care and devote a percentage of new housing to affordable units — basically helping existing residents stay in place instead of pushing them out.

“Sometimes those who work at these hip new restaurants can’t afford to eat the food they produce,” Sbicca said. “Most cool neighborhoods are cool because of their restaurants, but most of their workers can’t afford to live there.”

He added that free market forces can exacerbate the situation.

“People are voting with their dollar,” Sbicca said. “We can’t buy our way out of the problem. Many who consider themselves progressive are voting with their fork, and that can lead to displacement of people. The question becomes, ‘Who are we sustaining, and what are we sustaining?’”

Cities covered in the book include Portland, Oregon; Durham, North Carolina; Vancouver, British Columbia; Oakland, California; Oklahoma City; San Francisco; Chicago; and Cleveland.

Sbicca recently co-wrote an article about food and gentrification for The Conversation with his two co-editors. He is also the author of Food Justice Now! Deepening the Roots of Social Struggle, which was published in 2018.